Sensorial perception of the world is an essential ability of living creatures; a condition for survival. Observing the world beyond this necessary level and creating representations of the observed correlations are specifically part of human behavior. Making use of this ability, on the occasion of a profoundly personal experience – the birth of my son – I was able to experience the fact that nature uses the same time-tested structures in the most diverse forms of life.

The quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) is one of the oldest living creatures in the world. One of its colonies in Utah, known as Pando, is estimated to be more than eighty thousand years old. Multiplying through rhizomes, it creates a large forest that is considered a single living organism due to its shared root system. The individual trees spring up and wither, but life is uninterrupted in the roots. All this coincides with a strange dream I had about Buddha sitting in the lotus position, holding and breastfeeding two smaller Buddhas. In their turn, these Buddhas also breastfed two even smaller Buddhas, and so on, indefinitely, similarly to the Buddhabrot fractal. Advanced image generation techniques present us with a dilemma. How far should we stray in our quest to keep finding out more about the human embryo’s life in the womb? My wife and I took part with great interest in numerous ultrasound and other investigations during pregnancy, learning about the child’s gender in the process as well. We tried to gather all the information we could to monitor the health and development of our child. At the beginning of the pregnancy, I refused the idea of being present at birth as I can’t stand the sight of blood. However, nine months were long enough to make me change my mind. Today, I’m really glad that I was able to participate, physically, intellectually and spiritually, in the bringing into the world of our child.

I had learned about the role of the placenta only a few days before the birth. The experience and the discovery of correlations were absolutely overwhelming. I believe that if we are able to appropriately process the corporeality manifested with such emotional intensity in the rite of birth, we may gain valuable insight into the nature of life itself by interpreting the role of the placenta.

In the embryonic phase of life, we are all fed through the umbilical cord and the placenta, which is an intermediary organ that belongs to the embryo. Still, this organ that plays such a vital role in the preservation of our species gets undeservedly little attention in our days. For me, acknowledging its importance was an experience that went far beyond the biological considerations. Where is the point where I end and you begin? The fetus is fed through the mediation of the placenta and it sends the residual matter back to the maternal body through the same channel. The mission of the placenta extends for nine months, until the moment of birth, feeding the embryo until the first breath is drawn. When its mission is completed, the maternal body lets it go, and it is detached from the uterine wall.

At birth, the baby is the first to come into the world, followed by the placenta. Different cultures have different solutions for disposing of this intermediary organ after it loses its primary function. In some cases, the placenta is consumed, while in others, a tree is planted over it or it is recycled as compost. The rituals of disposal are all influenced by the fast decomposition of the organ. For a while, it was standard hospital procedure to reuse the placenta for cosmetic purposes, but these practices were replaced by incineration, due to the danger of contamination. The umbilical cord is sometimes cut only after the mother has given birth to the placenta as well, letting the organic bond between the baby, the umbilical cord and the placenta persist for a while even after birth. During the so-called “lotus birth“, the umbilical cord is not cut at all, letting the baby stay connected with the placenta until the umbilical cord dries off naturally.

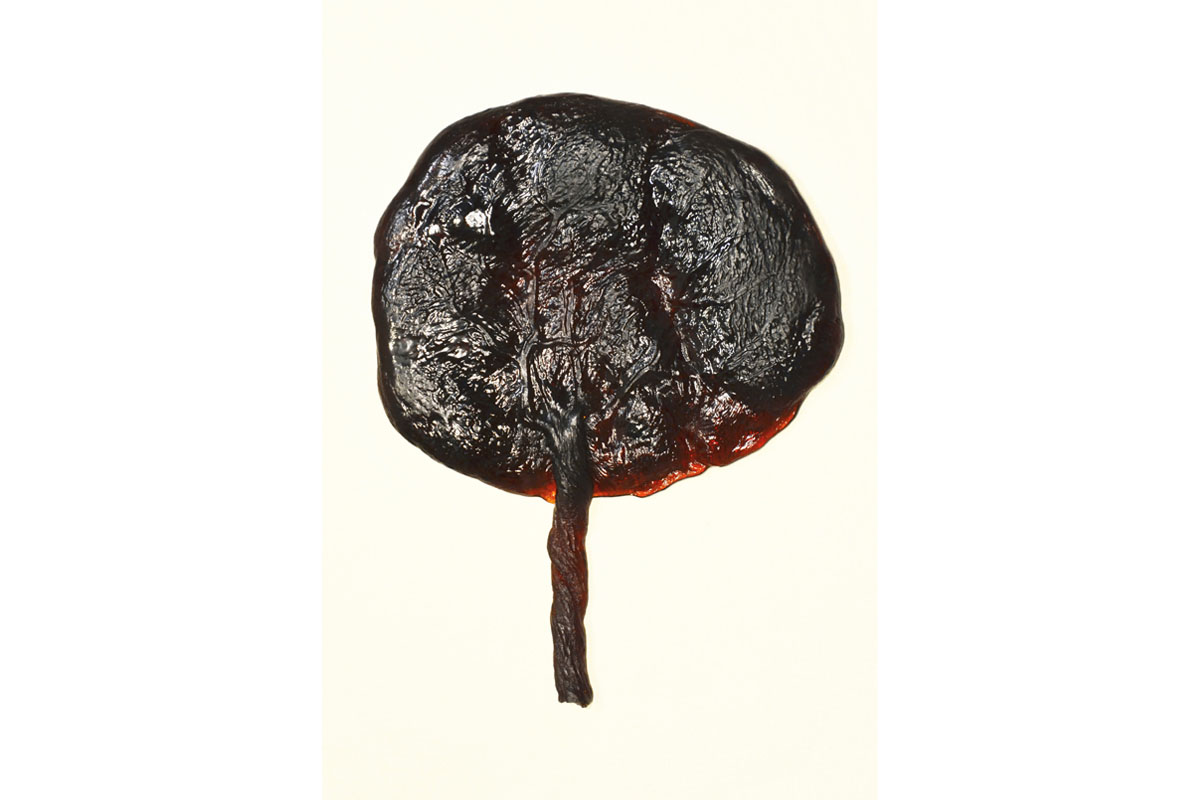

At the birth of our child, the custom at the hospital was that the father cut the umbilical cord, and then the mother gave birth to the placenta, which the doctor examined and presented to the parents before discarding it to be incinerated as hazardous waste. All this goes to show that this organ of intermediation, the tangible and symbolic evidence of our interconnectedness, has no place in modern life. Opposing the custom, we asked that the placenta not be thrown away. After receiving it, I used it to make direct prints and then I preserved it by freezing. Later, I prepared a mother mold of the organ, which I used for making a cast of colophony. My analogy is the tree, where the roots represent the main, secondary and capillary vessels, the trunk is the umbilical cord, and the crown is the fetus. As it is a kind of resin, colophony is the blood of the tree. This analogy may help understand why people are so deeply attached to trees on an emotional and spiritual level. Our very first sensory relationship is established with a vital organ that has a very similar structure to a tree. My mother planted a sycamore sapling in their garden on top of the placenta of our son.

Herta Müller said in an interview: “Trees have roots; people have legs to walk on, or to run, whenever it becomes necessary“.1 I believe that we, humans, are trees as well. Our first and direct root is nourished by our mother’s body. However, the position of the root-trunk-crown structure changes together with the mother’s movements. Unlike trees, people must be constantly on the move to maintain a nourishing environment.

Let us imagine what would happen if the umbilical connection between the mother and the child wasn’t interrupted after birth, and we formed endless colonies by remaining connected to our mother.

The biological and spiritual feeding circle of human life is best represented by three Y-connections. The first one ensures the direct connection with the blood circulation of the mother through the placenta and the umbilical cord and an indirect connection with the outside world. The second one is observable in the transient situation of breastfeeding, during which there is a direct connection with the mother, and the process of discovering the outside world begins. Here, the breast plays a similar role to that of the placenta, while resembling structurally as well (nipple, galactophores, lactic duct, mammary gland lobes, etc.). Finally, the third Y begins and ends together with the weaning process. The direct connection with the world is made possible by the knowledge acquired during the development of intelligence. The child gradually discovers that he/she and the mother are separate entities. The child’s physical, emotional and spiritual evolution guides him/her into adulthood, when he/she separates from the parents, becoming an independent carrier able to pass life on. The ruthless instinct of preservation subdues us humans through hardwired desires, making sure that the story does not end.

In our society, the state regulates the way we enter and leave the community. Where the state takes over the “burdens“ of birth and death, man may become vulnerable in the absence of adequate rites. The function of rites is to make the unbearable bearable, to help us through difficult moments and to interpret experiences that are difficult to understand. How to handle the issues around birth? What to acknowledge and what to ignore? What is the right place for these things in our life? These are some of the questions we must ask. In our “civilized“ society the placenta has no place – the intermediary is “untouchable“.

If we pay attention to the intermediary role of the placenta, we will realize that, in a sense, we are nothing but carriers ourselves. Individualism suggests that we should think of ourselves as separate entities, which is undoubtedly true. However, our existence would be impossible without the forest of society that functions as a gigantic organism. We are nothing but passing shoots of a network of roots that is spread out through the world. Considering all this, we can see that the connections between us are stronger than our everyday behavior would suggest. The placenta teaches us that we are the primary, secondary and capillary roots of the same trunk.

In general, we experience reality through the social norms we follow, even though a deeper understanding requires a much more open perception. My direct prints, the Colophonium Placenta and the sycamore tree planted on top of the placenta are intended to replace the practices established in modern society with a more conscious gesture, as well as to emphasize the role of the neglected placenta. Through my work, I am trying to make the correlations I discovered perceivable to others, and to express my belief that the place of this organ is not in the garbage bin.

(Translated by Alex Moldovan and Zoltán Móra-Ormai)

1. Herta Müller – Váradi Júlia, “Én nem akartam disszidens lenni“, Élet és Irodalom, 30 November 2012.