The three benches were made by reclaiming the window and door frames of an old press house, as a place of contemplation for the smallest democratic community.

The giant oak silk moth (Antheraea yamamai) originates from Southeast Asia. In Europe, it is an invasive species, whose appearance on the continent is the result of human activity. It is not a protected species in Hungary. In 1866, Johann Mach imported oak silk moth eggs from Japan to start silk production in Veliki Slatnik (then part of the Habsburg Empire, nowadays in Slovenia). The enterprise was a failure; however, the eggs hatched and the moths conquered their new habitat. Upon having crossed illegally into the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1868, the moths began to proliferate in great numbers. According to our present knowledge, the species does not pose any threat to our ecological system and it does not cause any environmental damage. The artwork is the imprint of the butterfly. The cast is a negative taken from its two sides, an exquisitely drawn open shape that showcases the absence of the moth, resembling the Moon in the first quarter — the species is invasive, while the Moon is waxing.

The silk moth and the western honey bee are both domesticated insects. I have worked with bees before, in the context of the geometry of ideal living spaces (In the apiary, 2010-2014). However, now I am presenting the nature of these insects from a new perspective, one that is essential for their survival, but sheds a different light on their society. According to common perception, bees are respectable creatures due to their diligence, self-sacrifice and thrifty prudence. We see bees as moral examples, especially as regards their built environment: the queen bee and the swarm leave the beehive behind to give space for the next generation. In the same time, their society falls way short of being ideal as they can be easily tricked by humans and the moral construction falters when applied to the phenomenon of drone eviction.

The drones are male bees, responsible for the fertilization of the queen bee. In addition, they actively contribute to balancing the temperature of the beehive by generating heat through continuous shivering or cooling the air by fanning with their wings. The drones are ‘useful’ during the abundant summer, but become ‘useless’ in the dearth of winter. Their numbers are regulated by the colony through brooding and later through eviction.

Because drones do not collect pollen, do not play a part in feeding the next generation or build the hive, which, in a bee colony are the responsibilities of the working bees, who are the infertile females, they are perceived as ‘lazy’. In vernacular speech lazy people are referred to as ‘useless drones’, though the expression is inaccurate. Even if humans do not directly gain anything from the activity of drones, it is indispensable for the reproduction of bee families.

The eviction is a yearly event in the lives of bee families. In autumn, the now unnecessary drones are evicted from the hives ‘without mercy’ by the working bees. They are pushed out and not let back inside to eat, until they eventually starve to death. Obviously, this is not a ‘ruthless’ intervention by the workers as it is an instinctive action taken in the interest of the colony. However, if a society does not know mercy, then it cannot be called ideal, at least not in the human sense.

It should be noted that when the bees do ‘good’ according to our moral standards, we use them in our parables, but when they do ‘bad’, we cease to identify with them and point to their instincts.

In 2016, the event of drone eviction coincided with the campaign of the referendum on refugees in Hungary. The refugees coming to Europe now have never directly formed a part of the communities in the countries they wish to enter; however, the same European countries had been exploiting their habitat for a long time. These territories are mostly former colonies, whose communities used to ‘fertilize’ the cultures of their colonizers — whom they plead for refuge in these times of crisis. With the referendum, the Hungarian government aimed to legitimize its decision of denying access to refugees, labeling them as dangerous for their hosting countries. Without a doubt, the management of this crisis is a complex challenge; however, the workings of human society are not exclusively based on laws of nature. Their leaders must make a moral decision whether to urge their people to act out of fear, refusing to help, or out of a sense of responsible good-will towards those in need.

Pollinating animals such as wasps are responsible for the growth of crops in many ways. As such, their diminishing numbers pose a serious threat to the wellbeing of human society. In spite of this, wasps still induce a feeling of fear in people who usually try to exterminate them whenever they find their nests. The nest on the picture was taken from a building, a human environment, wishing to preserve something that we usually destroy.

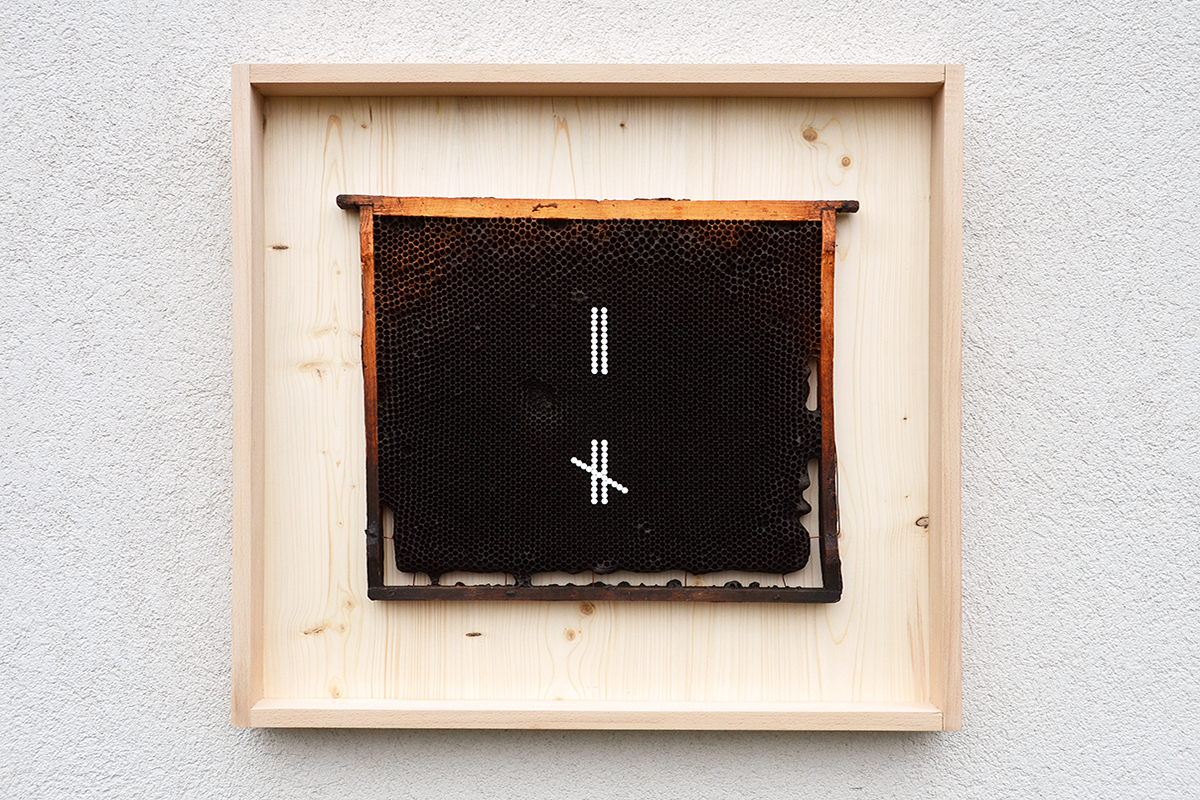

The beehive is a human invention. Replacing the skep basket (which, in turn, was invented to replace natural cavities in trees and rocks), it makes it possible to retrieve honey without completely destroying the combs. In addition to bees, hives can be inhabited by hornets and wasps as well even though they all use honeycombs of different sizes. The European hornet is the largest species of wasp found in our area, while the Saxon wasp is much smaller in size. In Hungary, neither species enjoys legal protection, as opposed to Germany. People generally regard their nests as a form of pest infection producing alien cells in the system. The picture shows a hornet nest built between frames left behind in an empty beehive, inhabiting the structure designed and built by humans. The second picture shows a structure constructed by Saxon wasps upon the combs of honeybees. Both structures have been created as a result of interplay — organic constructions in an environment built by humans. We usually destroy and burn their nests as we cannot exploit hornets and wasps for the purposes of honey production. Acknowledging the importance of their role in the local ecosystem is a matter of understanding.

Three hands of the same quality, out of the same paper, indicating the sign of victory. The Saxon wasp builds its spherical nest from this grey paper-like material, using birch bark and discarded paper. The nest is striped due to the variety of materials and construction methods applied. I took this material and formed three hands indicating the sign of victory. Two of them are upright, but the third one is upside down, as if stepping over the others in victory, representing a kind of hierarchy, but connecting them in the same time. I placed a small bit of a wasp nest, reminiscent of a crowned heart, in the space created in the middle.

We have two independent units, two parallel sections. We know them as the sign of equality, and yet, the equal is not equal. As it is constructed, the dual sign presupposes a hierarchical relationship in which it sub-ordinates or co-ordinates its own unit. Depending on their positioning on the vertical or the horizontal axis, or in any angle, one of the lines will always be seen as being above or in front of the other one. Therefore, equality is missing even from the symbol chosen to represent the concept.

There is no equality in real life either, even if certain measurable characteristics, such as weight, length or time, may be of the same extent. Equality is nothing more than an abstract concept denoting certain relationships, the illustration of which is next to impossible in the dimensions known to us. If a subordinated thing could be at the top in the same time, or if the first could be the second as well, only then would this symbol illustrate the concept accurately. As long as this is not possible, because the condition of equality does not exist in our reality, we cannot construe an adequate symbol either.

September is the time for the deer troat, when male deers make deep and loud sounds to attract females. It is also hunting season for deers. The hunters crave the meat and the antlers of their pray, usually discarding the feet. I found a photo in the Museum of the Iron Curtain in Felsőcsatár, showing a kind of shoe made by attaching animal feet to wooden soles. The object is the embodiment of a naive idea: the person wore these shoes in the hope of misleading the border guards and crossing the border between Hungary and Austria undetected — an attempt punishable by death at the time if unsuccessful. These shoes could be worn backwards as well, to make sure that an actual hunter does not follow their footprints by mistake. The so called ‘technical barrier’, meant to prevent illegal border crossing, included a strip of dirt or sand that was raked every day to detect any new footprints. However, border guards did not only pay attention to the direction of the footprints, but to the direction in which the soil was ejected as well, neutralizing the idea of the shoe worn backwards. I took the idea and applied it to our times, making several shoes in the process, which carry the metaphorical meaning of invisibility, the idea of free crossing. By inspecting them, we can imagine the hunting scene where someone is being chased by members of their own species, in a sense turning the victim into an animal who needs to hide in ‘nature’. Such scenes usually occur between members of different species, where an animal traces the footprints of another, hunting it for food. Not here though — the border guard who notices a human footprint will chase, capture or kill the person trying to cross the border in the name of the ‘higher order’ of protecting a territory that is not even his or her personal habitat. The person who violates the border returns to the animal kingdom, hoping that the fake footprints would make him or her irrelevant and thus invisible for the border guard. I wish to commemorate this hope through these shoes.

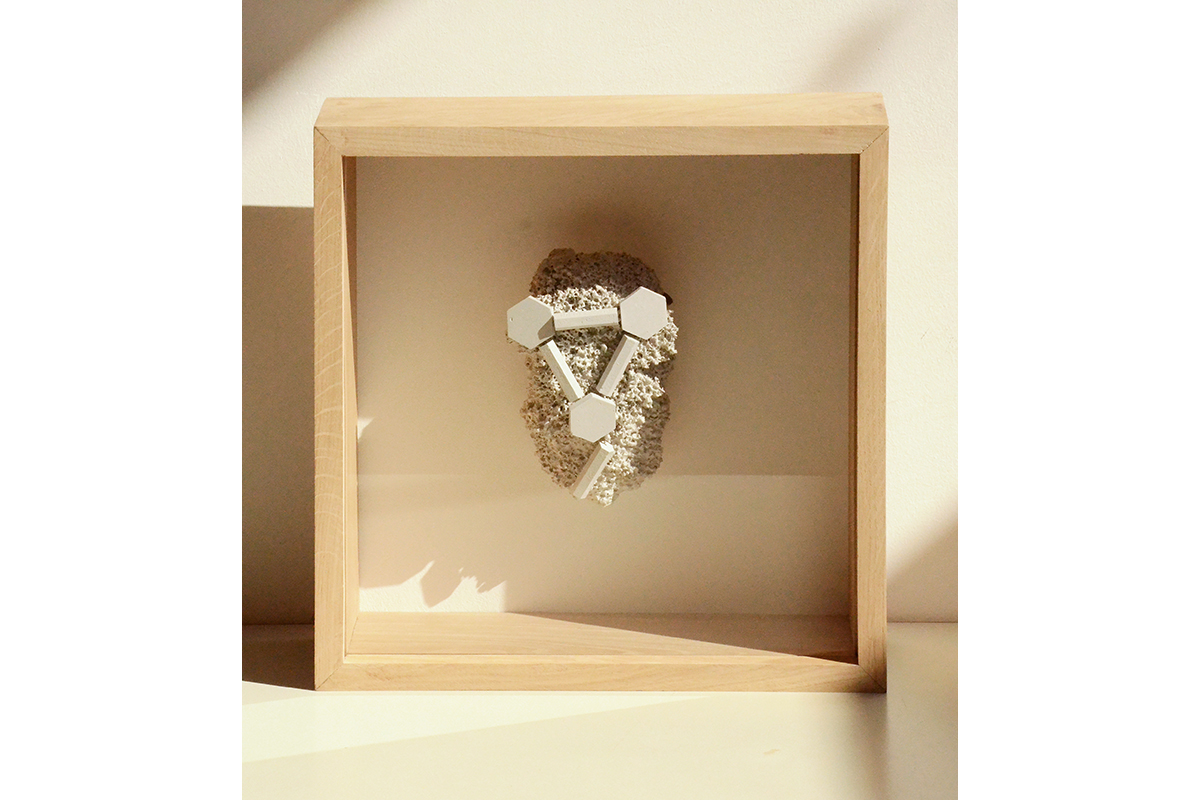

A heavy hailstorm affected the vineyard on the 15th of August, causing serious damage (locals said that the ice fell because they were working on a Sunday). I filled a bucket with the ice and made an imprint by pushing my face into it. As the ice was melting quickly, I poured gypsum over the ice, filling up the porous surface between the crystals and forming this strange, coral–like self-portrait.

In an earlier stage of ice formation in the atmosphere, humidity solidifies into floating hexagonal ice crystals. I enlarged the columns and plates that form these crystals, and used them to write a kind of formula, similar to a chemical bond. The bonds represent the smallest possible social model on the top of my self-portrait. A well-balanced personality is mostly created by other people, rather than having a unified self.

What we see here are two different manifestations and interpretations of ice —a promise and a punishment. The light reflected on the smallest crystals seals the promise that there will be rain, but the world will not be destroyed by flooding (Genesis 9), while the other manifestation is punishment in the form of hail.